R Setup

# Data manipulation

library(dplyr)

library(purrr)

library(tidyr)

# Modeling

library(broom)

# Plotting and tables

library(ggplot2)

library(patchwork)

library(ggthemes)

library(knitr)

# R settings

theme_set(theme_tufte() + theme(legend.position = "none"))

opts_chunk$set(echo = T, warning = F, message = F, tidy = F,

fig.width = 8.5, fig.height = 6)Introduction

In his 2011 paper “Land tenure and investment incentives: Evidence from West Africa,” James Fenske notes that “studies that use binary investment measures…are also less likely to find a statistically significant effect.” He seems to attribute this to (1) small sample sizes, and (2) the lack of nuance associated with binary variables. Fenske argues that continuous measures of investment intensity are better for causal analysis. As Fenske points out continuous variables are usually noisy. For example, imagine asking a farmer how many KGs of fertilizer they applied to each plot of land in the past year versus asking a farmer if they applied any fertilizer to each plot of land in the past year.

While small sample sizes can certainly cause estimation issues (frequentist statistics rely heavily on asymptotic results afterall), I’d like to explore why binary variables may be showing up more often as statistically insignificant in this context.

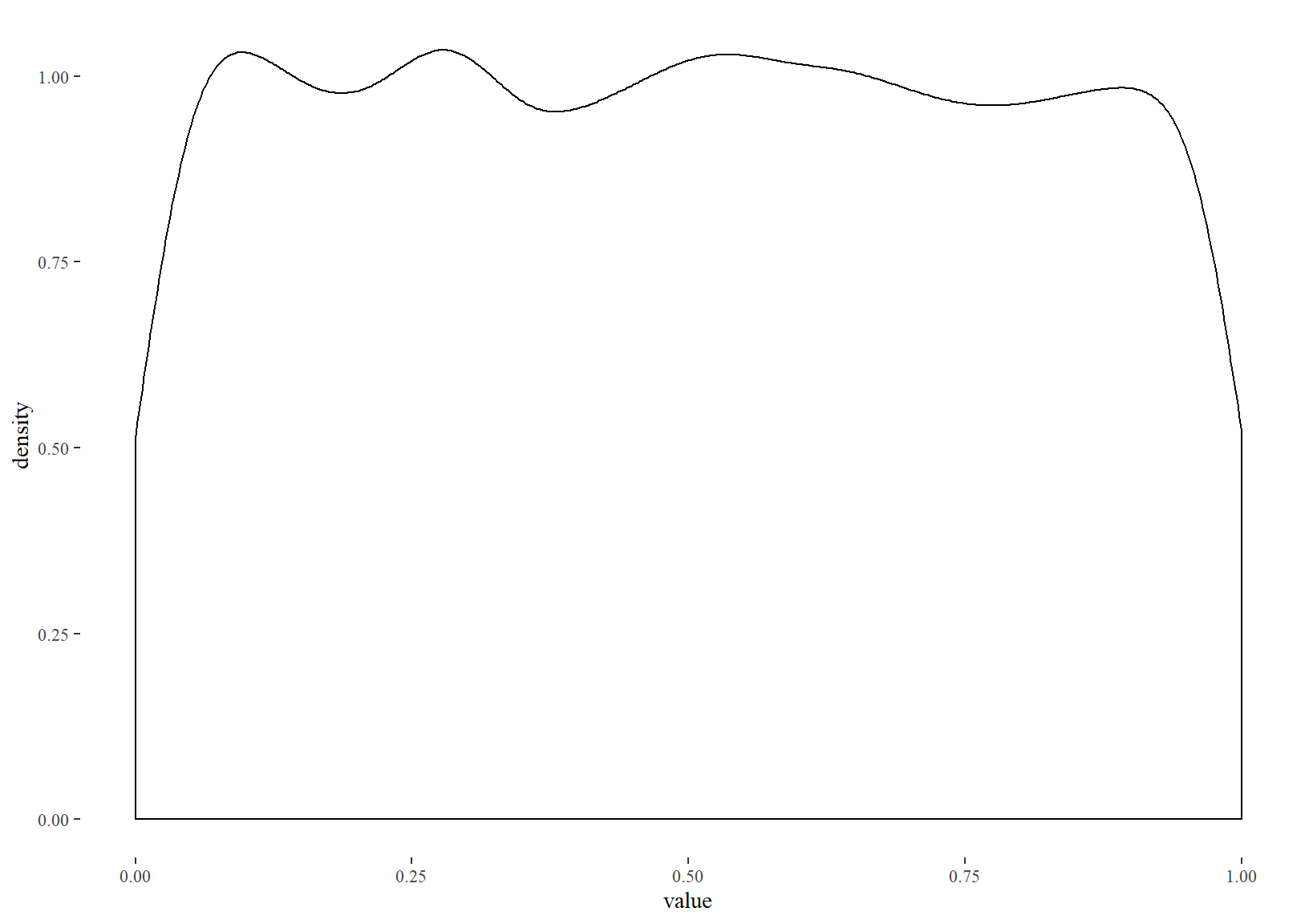

This post should come with the standard caveat that p-values are flawed, and that any time a large number of significance tests are run there will be false-positives. For example, the distribution of p-values obtained by comparing identical normal samples is uniform:

map_dbl(1:10000, ~ t.test(rnorm(1000), rnorm(1000))$p.value) %>%

as_tibble() %>%

ggplot(aes(value)) +

geom_density()

I will also be assuming the use of OLS rather than logistic regression, which is somewhat common in the economics literature for binary variables. I will write in terms of fertilizer amount (continuous) /fertilizer use (binary) and a treatment meant to increase fertilizer use, but these results generalize.

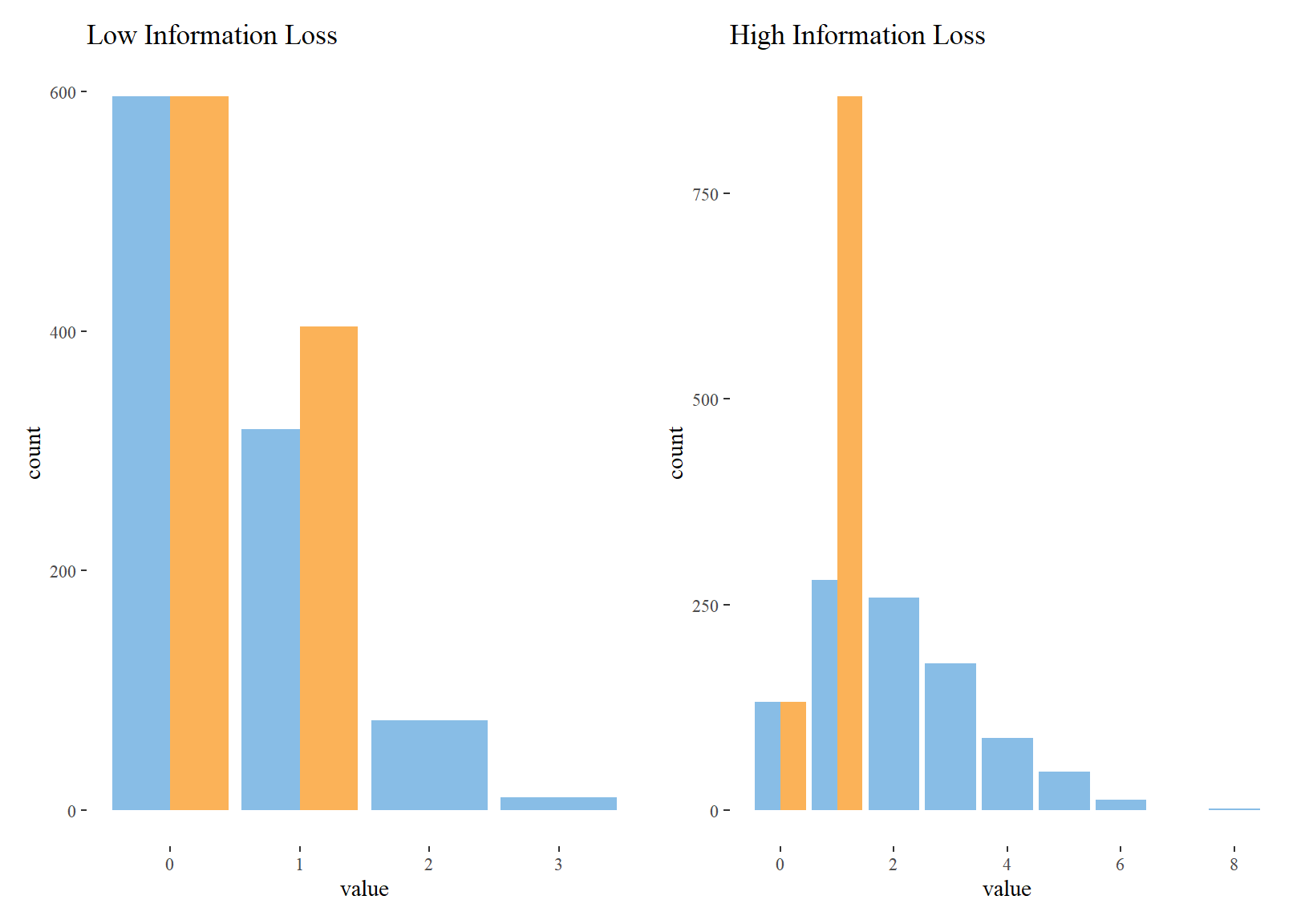

Information Loss

Binarizing a continuous variable, even if noisy, will result in some amount of information loss. As Fenske points out, we go from estimating the amount of fertilizer used to an indicator for any fertilizer use. If few farmers use fertilizer to begin with, then information loss will be low. That is, we can still tell the difference between farmers who fertilize, and those who don’t. However, if most farmers use some amount of fertilizer, then the binarization will make it very difficult to test for any treatment effect.

# Simulate information loss

tibble(

y = rpois(1000, 0.5),

y_bin = ifelse(y > 0, 1, 0)

) %>%

gather(variable, value) %>%

ggplot(aes(value, fill = variable)) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge") +

labs(title = "Low Information Loss") +

scale_fill_few() -> p1

tibble(

y = rpois(1000, 2),

y_bin = ifelse(y > 0, 1, 0)

) %>%

gather(variable, value) %>%

ggplot(aes(value, fill = variable)) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge") +

labs(title = "High Information Loss") +

scale_fill_few() -> p2

p1 + p2

Simulations

I will be using simulations to explore this issue. Data will be drawn from a Poisson distribution, which has mean equal to its only parameter, lambda. This is quite convenient for simulating treatment effects, as we can easily increase the treatment effect by shifting lambda.

sim_settings <- expand_grid(

# Number of repeats for each group of simulation settings

m = 1:5,

# Sample size

n = seq(100, 3000, 100),

# Lambda (mean of Poisson)

lambda = c(0.5, 1, 1.5),

# Treatment effect in absolute terms

# (i.e. added to lambda)

treat_effect = seq(0.01, 0.2, 0.05)

)

sims <- pmap_df(sim_settings, function(m, n, lambda, treat_effect) {

# Generate data

treat <- rep(0:1, each = n/2)

y <- c(rpois(n/2, lambda), rpois(n/2, lambda + treat_effect))

y_bin <- ifelse(y > 0, 1, 0)

# Run models

bind_rows(

lm(y ~ treat) %>% tidy(),

lm(y_bin ~ treat) %>% tidy()

) %>%

filter(term == "treat") %>%

mutate(m = m, n = n, lambda = lambda, treat_effect = treat_effect,

outcome = c("continuous", "binary"))

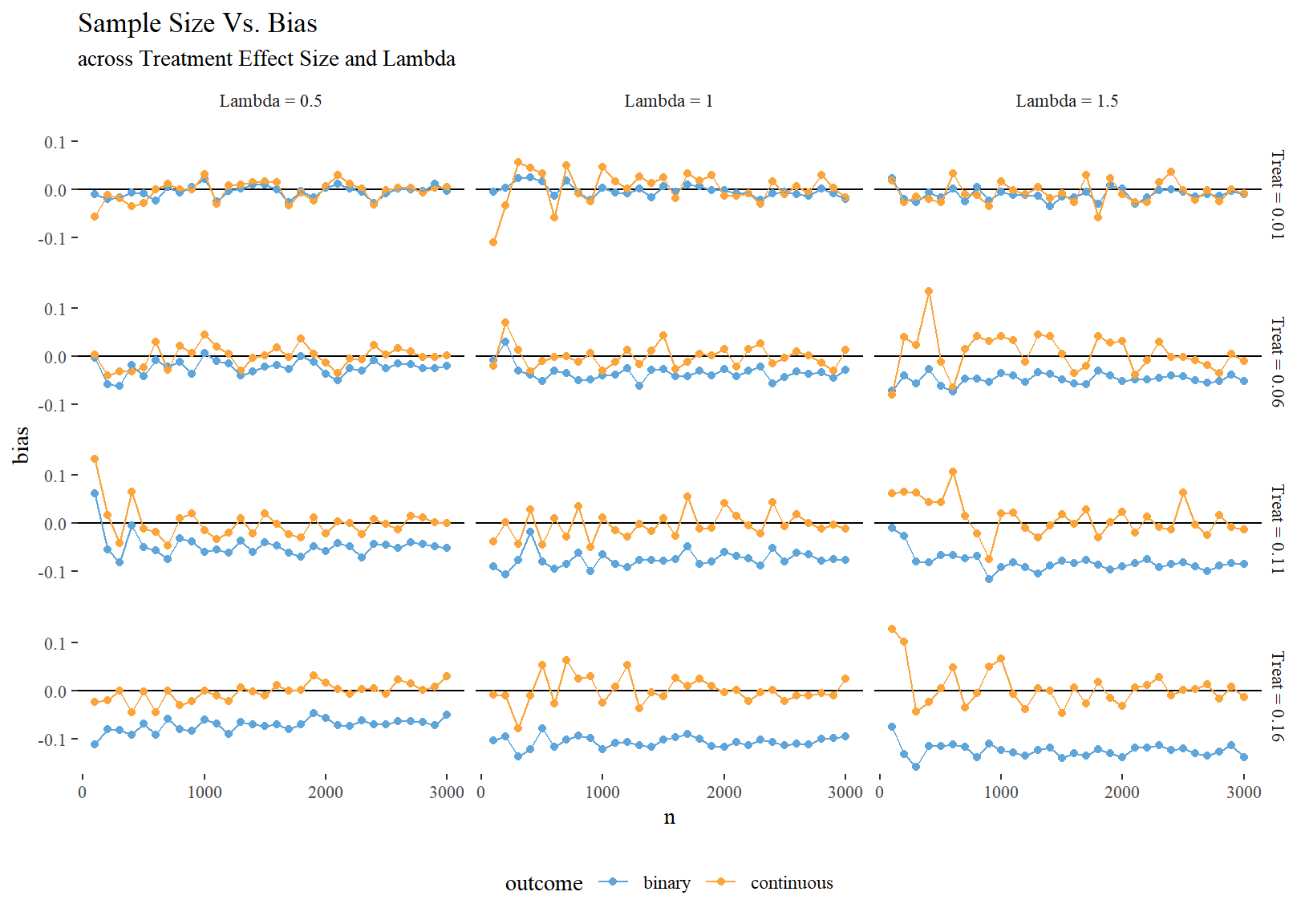

})Binarization will cause issues estimating a precise treatment effect, with higher information loss (i.e. higher lambda) leading to more bias.

sims %>%

group_by(n, lambda, treat_effect, outcome) %>%

summarise(bias = mean(estimate - treat_effect)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(lambda = paste0("Lambda = ", lambda),

treat_effect = paste0("Treat = ", treat_effect)) %>%

ggplot(aes(n, bias, colour = outcome)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0.0) +

geom_point() +

geom_line() +

scale_colour_few() +

facet_grid(treat_effect ~ lambda) +

theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

labs(title = "Sample Size Vs. Bias",

subtitle = "across Treatment Effect Size and Lambda")

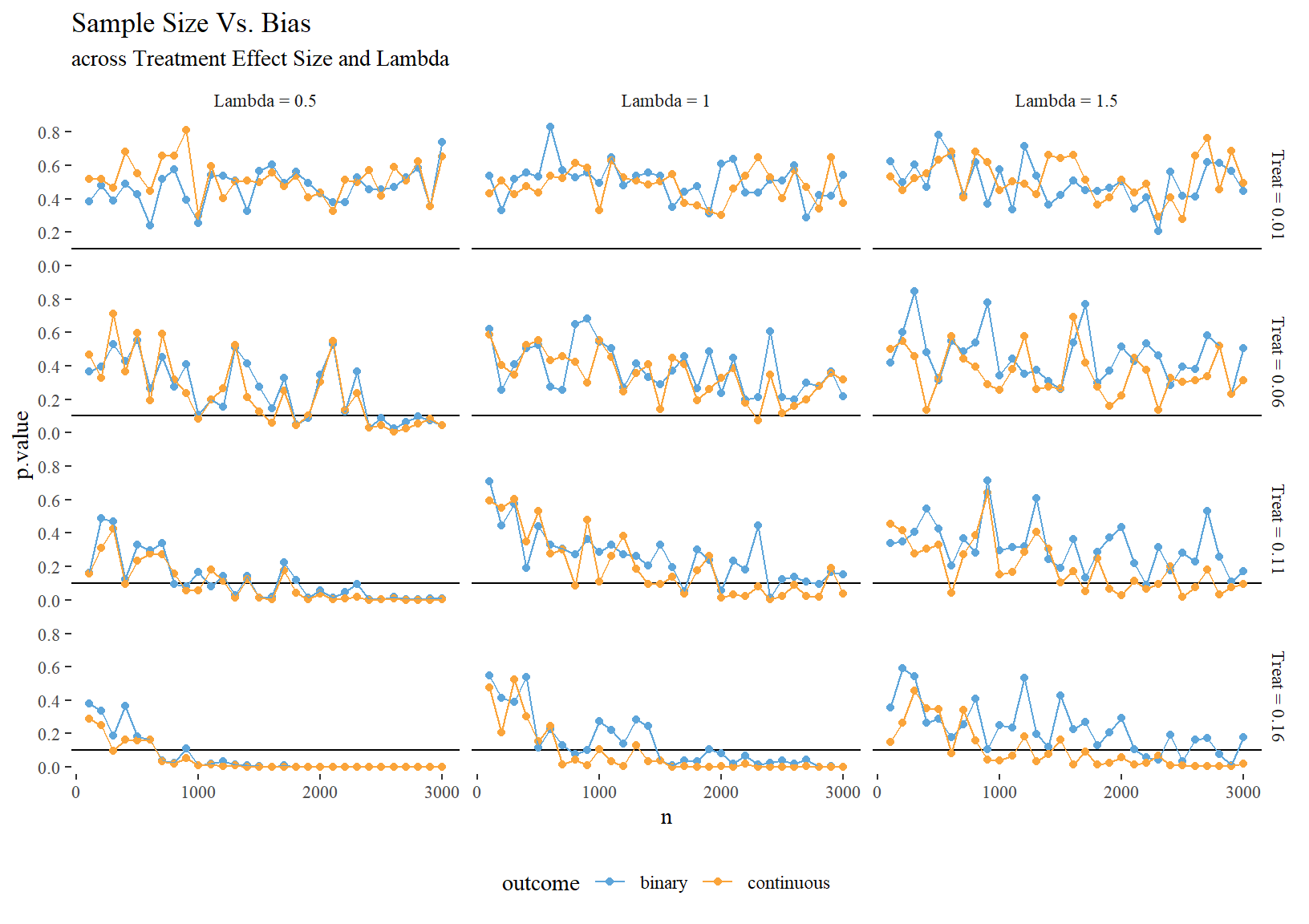

While effect size estimates are biased, they still seem to work well enough for significance testing in situations where information loss isn’t extreme.

sims %>%

group_by(n, lambda, treat_effect, outcome) %>%

summarise(p.value = mean(p.value)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(lambda = paste0("Lambda = ", lambda),

treat_effect = paste0("Treat = ", treat_effect)) %>%

ggplot(aes(n, p.value, colour = outcome)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0.1) +

geom_point() +

geom_line() +

scale_colour_few() +

facet_grid(treat_effect ~ lambda) +

theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

labs(title = "Sample Size Vs. Bias",

subtitle = "across Treatment Effect Size and Lambda")

Conclusion

I suspect Fenske is correct to question the use of binary investment indicators over continuous intensivity indicators. However, it is clear to me that binary indicators are fine for many situations, e.g. measuring the up-take of new agricultural technologies. For situations where the outcome is already common at a low level (and the sample size is high enough), a coarse grained intensivity measure may provide enough information to capture a reasonable estimate of the treatment effect.